My Brutalist. Can one person's fiction be another person's truth?

“The Brutalist” doesn't appeal to everyone. But in my case, the film hits home, like an old family photograph. Why is that?

I have been wanting to write a newsletter on “The Brutalist” ever since I went to see the film projected on celluloid a month ago. Admittedly, the constant stream of enthusiastic reviews along with a fair share of criticism kept putting me off. While the film is packed with great cinematic nuggets, critics were often frustrated with film in its ensemble: the architecture was considered barely credible; the American capitalists were walking clichés; the Hungarian accents were outlandish or overdubbed with the help of AI; and there were too many storylines that went unresolved.

But my reaction to the film was quite the opposite, as if I had watched another film entirely. I’m an architect who didn’t find the architecture that unbelievable. I thought the film’s portrayal of American capitalism was on the money. As the son of Hungarian Jewish parents, born and raised in New York, I can’t say the heavy accents were that far off either. I can remember listening to my father and his friends as they enjoyed singing and joking around the dinner table in Hungarian, and their English sounded much the same. And as for unresolved storylines, neither my mother, nor my father, nor any of our close surviving relatives were willing to divulge everything they endured during the war. I have been left with only fragments of their memories.

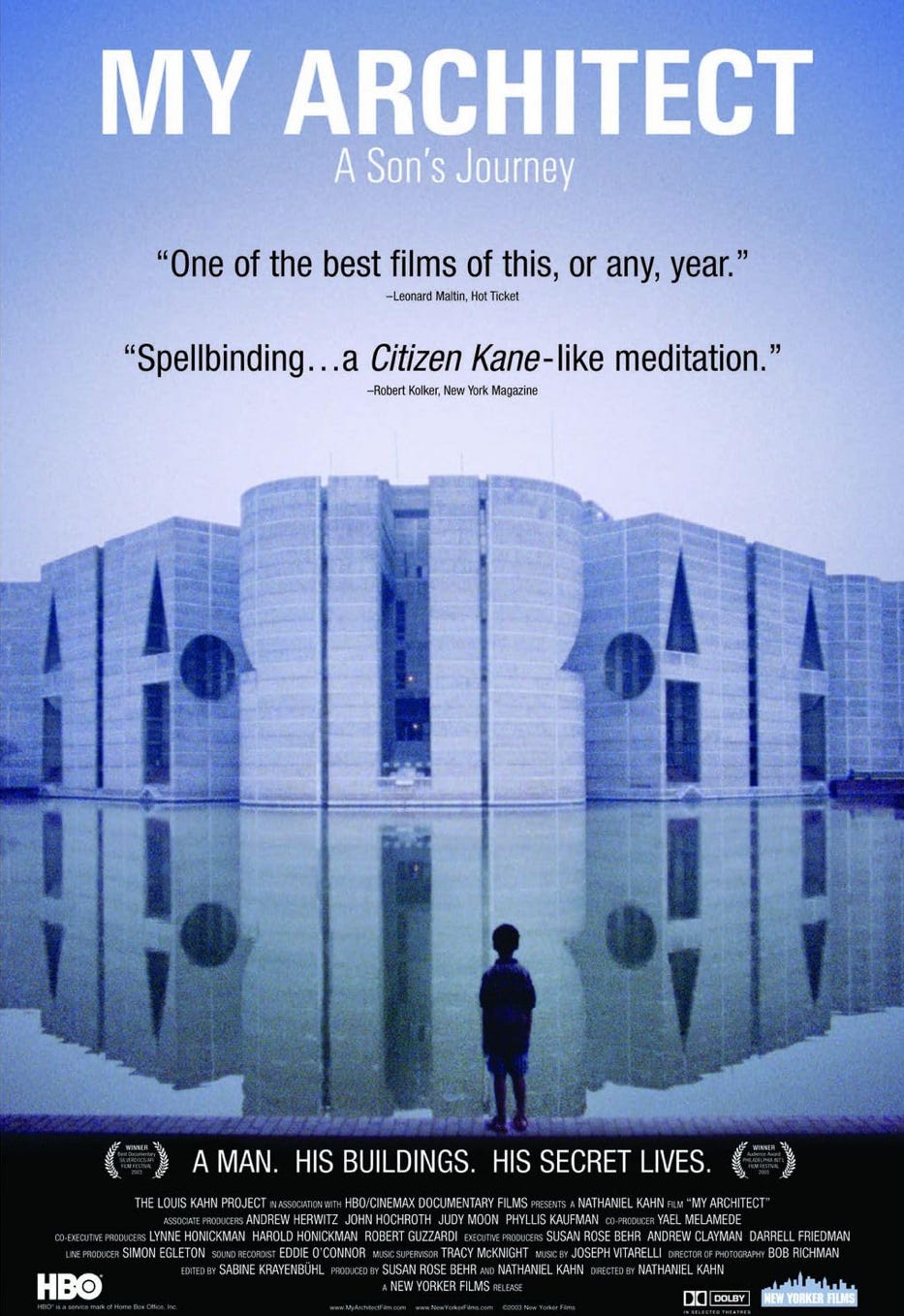

While some critics sought to find traces of László Toth’s obsessive character in the likes of other immigrant Bauhaus architects like Marcel Breuer or Walter Gropius, I found the film reminded me instead of the great 20th century architect Louis Kahn as he was portrayed in the 2003 docufilm “My Architect.” Though Louis Kahn was of Jewish Estonian origin, and his family migrated to the US well before Europe’s great conflicts, his early life was marked by poverty and family hardship. Louis Kahn’s estranged son, Nathaniel Kahn, who hardly knew his father, reconstructed the architect’s life as a way of coming to terms with his own troubled identity.

So the way I see it, the film “The Brutalist” is my Brutalist, and though it is written by Brady Corbet and Mona Fastvold, their storyline is in many ways uncannily similar to mine. Watching Adrien Brody embody this fictionalized László Toth as an angst ridden visionary hit a nerve, provoking me to reflect on my own family history.

To be sure, the hunt for the seminal origins of Adrien Brody’s character László Toth isn’t actually that difficult a thing to do. For one, the very name that was chosen for this character, László Toth, is loaded with significance. Though a very common Hungarian name, there was one individual László Toth who infamously took a hammer to Michelangelo’s Pietà inside Saint Peter’s Basilica. A disgruntled geologist who left Hungary and eventually ended up living in Rome, László Toth thought he was the chosen Christ, and in 1972, around his 33rd birthday, dressed in suit and bow tie, he whacked off marble bits of Michelangelo’s Carrara masterpiece.

There is a pattern that begins to emerge in Corbet’s and Fastvold’s brand of storytelling: things come together to form a weave from many different yet recognizable sources. The choice to name the main protagonist László Toth is one of the many formative elements in the larger story: Carrara marble is fetishized, destruction is rendered obscene yet enabling, and God is not in the details, but in the film’s celluloid.

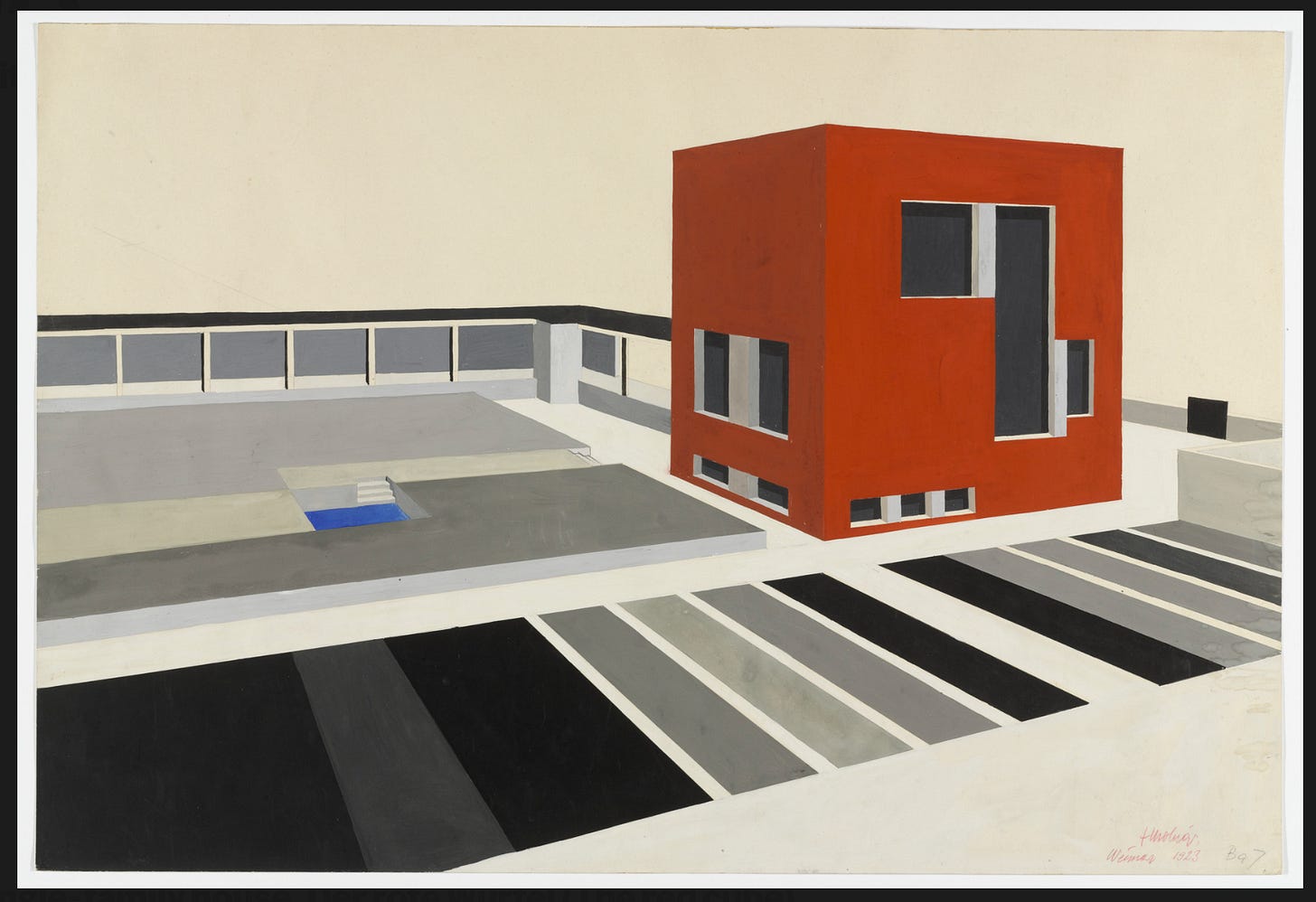

While most people refer to Jewish Hungarian Bauhaus trained architect Marcel Breuer as the obvious role model for Adrien Brody’s character, he isn’t the best match. Breuer was never the tragic figure. Its also been said that Brady Corbet consulted with the architectural historian Jean-Louis Cohen (*), to see if he knew any architectural personality from that troubled era that could serve his intentions, but Cohen couldn’t help. The character László Toth does seem in more than a few ways to resemble one real Hungarian architect, Farkas Molnar, who actually comes quite close to fitting the bill. He was a Bauhaus trained architect, well recognized by his peers, known for designing the “Red Cube House” while attending the Bauhaus. He also studied under Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. Molnar moved back to Hungary in 1925 where he launched his practice. Molnar did not suffer the same fate of the Hungarian Jews but he was killed in 1945 possibly during a bombardment in the final days during the bloody Siege of Budapest.

For me, The Brutalist story speaks about my own mother, Magda, who was living in Budapest at the same time but under completely different circumstances than Molnar. She secured a false identity to avoid deportation, and did her best to beat the odds and survive the vicious battles raging around her in the last months of the war. My mother wrote a diary that she kept hidden from everyone, and purposely left out details that if discovered would have certainly lead to her execution. She left Hungary for the United States immediately after the war, though she was unable to bring her mother with her. Hungary in the meantime became part of the Soviet block, and it took years to get my grandmother out of the country and over to the US. I found it very uncanny to witness the retelling of my mother’s story on the screen, the grainy Vistavision only confounding my own memories.

Then again, my father, Imre, like my mother who he would meet in New York some years later, managed to survive the war by his own wits, though he lost both his parents and his two sisters to the NAZI pogroms. He never put this part of his past aside. My father eventually left Europe for the States, he interned on Ellis Island, and in the process dropped the accent on the letter “á” from his last name. Once in New York, he decided to travel down to Allentown Pennsylvania to join his relatives.

It is this strange Vistavision déjàvu happening again. My father’s family in Allentown ran a furniture factory, and they offered him work in exchange for meals and lodging. But my father soon became, as he later told me, deeply disillusioned. There was an unbridgeable gap between his American family and himself as a war survivor. I can’t really speculate on the similarity between my father’s story and Lászlò Toth’s move to Philadelphia to live with his cousin and work in his furniture factory, but I found myself deeply moved by what could have almost been a reenactment of an early episode in my own father’s life as well.

Brady Corbet and Mona Fastvold succeed in their story telling by ignoring the obvious cinematic tropes. To portray the horrors of war they never once show it. For them, the best way to depict greatness is to focus on human weakness. László Toth’s namesake, who saw himself as the Christ figure who must destroy the beauty that gets between him and God, represents the impossibility of reaching one’s life goal. I can’t see the need to argue over the veracity of architecture as is depicted in this film because, like everything else about The Brutalist, architecture is made out as the symbol of unholy alliances. For architects, this film had no architecture, but this is to miss the point. The film is about Gestalt theory and the search for wholeness, one of the core principles that drove the early Bauhaus experiment. The character Toth speaks in the Gestalt language, but what we get instead is a bundle of inarticulate words.

The Brutalist suggests there is no wholeness possible. László Toth’s struggle to build a community center, like his struggle to reach God, is made out to be from the start an impossible task. Its like managing to build a working tower of Babel. No money in the world would succeed pulling it off. But if you see the film as an amalgam of many personal stories, mine included, it does indeed build a community.

(*) Jean-Louis Cohen’s life was cut short while he was still in his prime. I remember him fondly as my professor, and as a trusted confident. He has left us lots to ponder over his great legacy.

Errata corrige: Thanks to my Hungarian-American friend Ferenc Mechler for catching a mistake I made on identifying the location of the Community center in the photo. The center is in Nyiregyhaza, Hungary, not Nagymihaly in Slovakia. He also dug up the architect who designed this brutalist project from 1970: Ferenc Ban, and here is a link to Ban’s architectural photo gallery.