Why make a monument that is not monumental?

Now that my exhibition "Monuments counter Monuments" ended its run at the Embrice gallery in Rome, it's time to take a closer look at what the rethinking of monuments means to us today.

The show at the galleria Embrice in Rome “Monuments counter Monuments” closed with a public discussion that raised some basic questions on the meaning of monumentality today. True, monuments have become the targets of choice in the escalating cultural wars, but unlike other forms of public art that are more receptive to adaptation and innovation, the iconic monument isn’t geared to diverse communities or global cultures. There was some consensus among the participants in this final discussion that monuments were becoming an extinct art-form, so much so that they were becoming “invisible,” if not literally “inhospitable.”

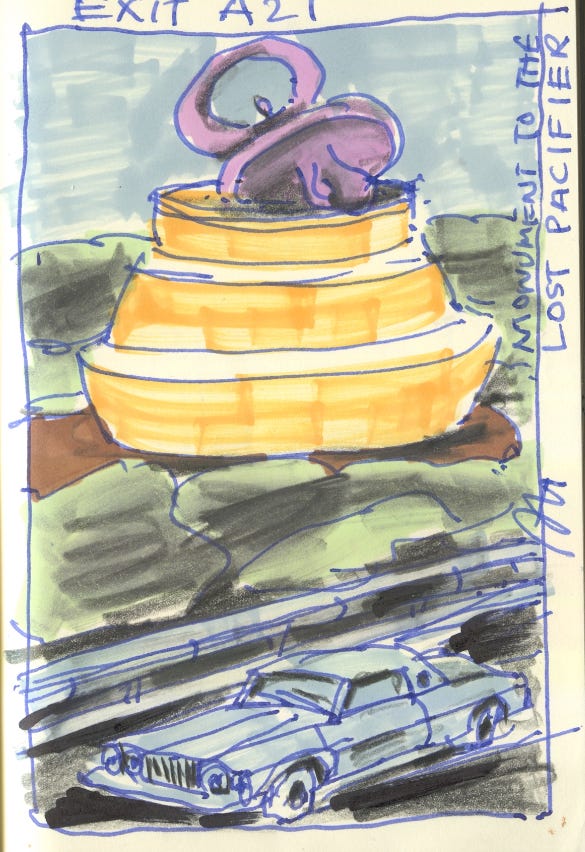

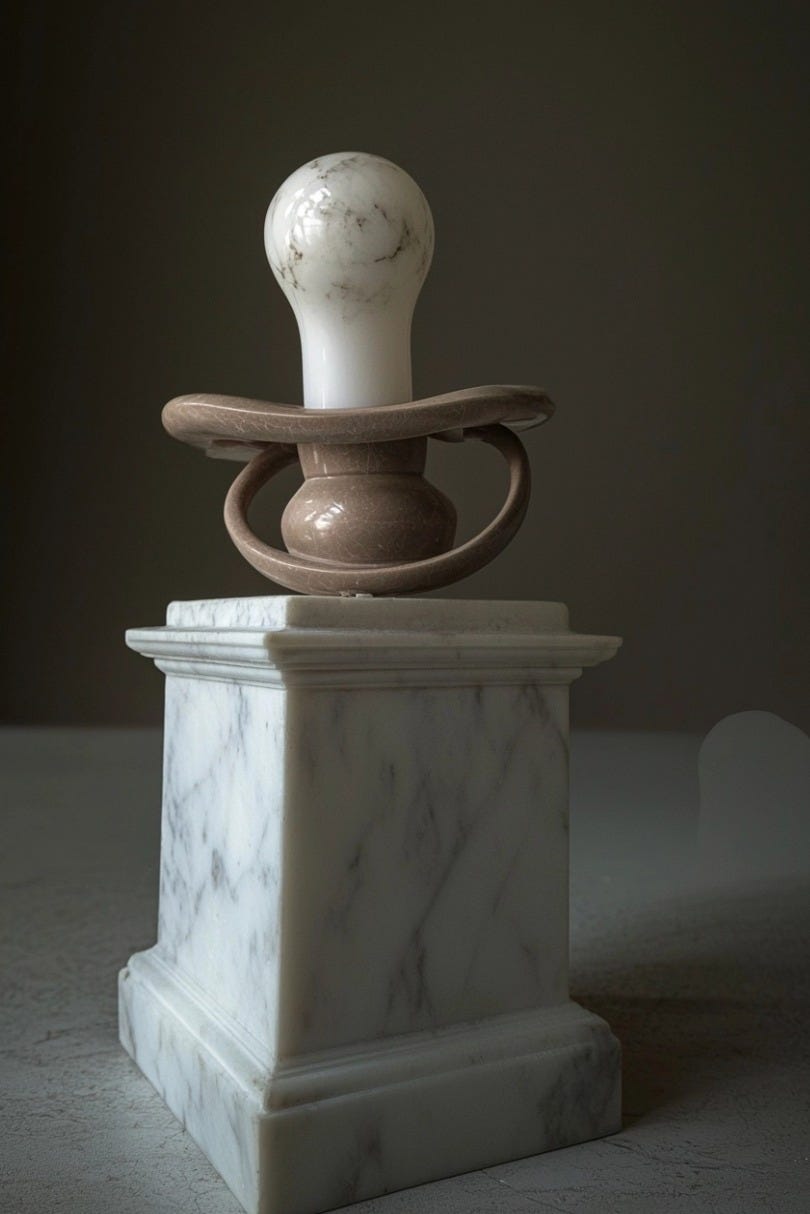

The exhibition on my recent work assembled for the Embrice gallery, curated by Carmelo Baglivo, was all about celebrating non-prodigious everyday things like doing the laundry, watching TV, getting a coffee, or having an anxiety attack. The exhibition’s overarching position, as I hope to clarify in this newsletter, is to fundamentally question how we as society are failing to come to terms with the concept itself of the monument as a public form of symbolic representation. And given the mounting crisis in monumentality, what are indeed the alternatives?

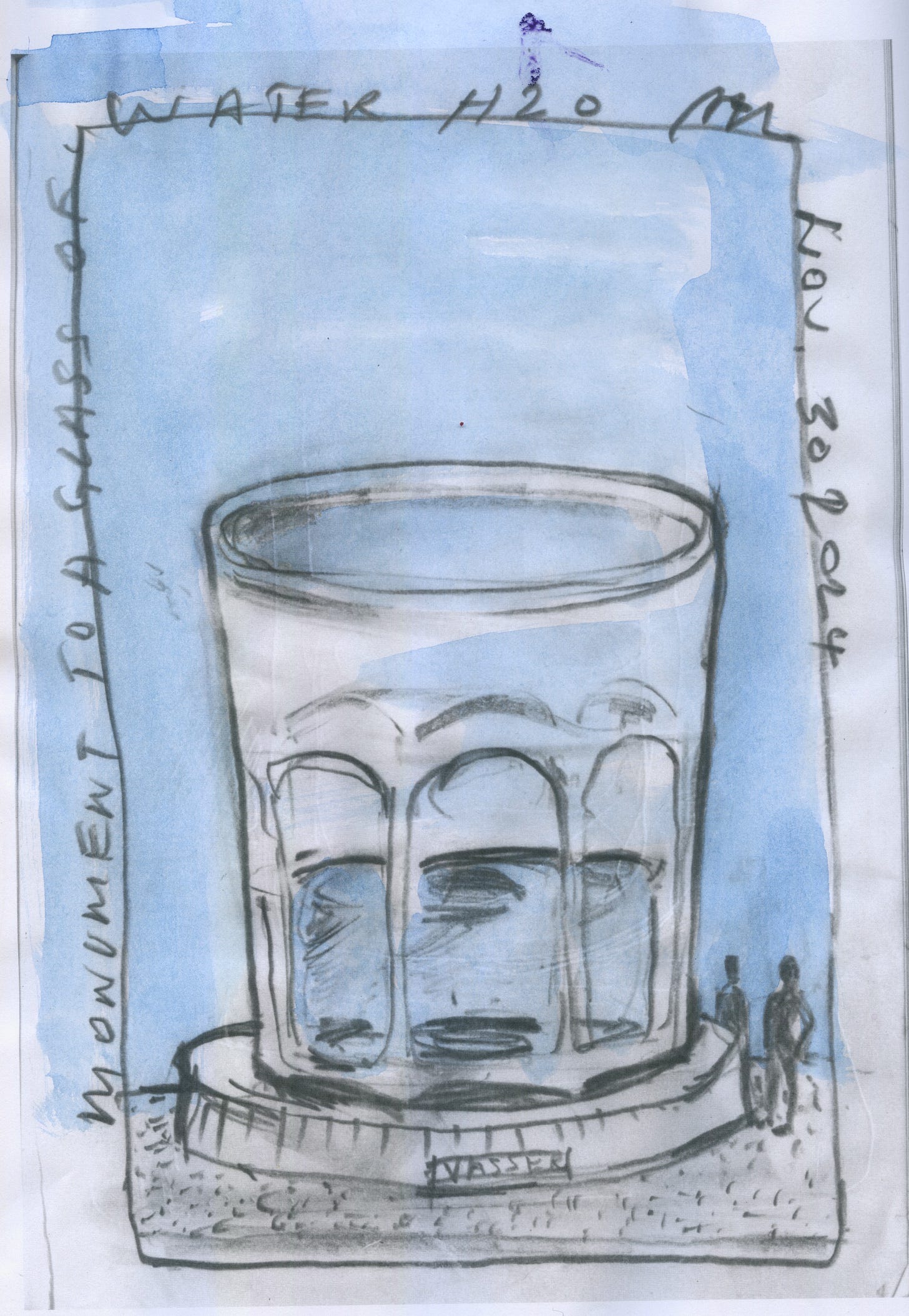

One monument I developed for this project, the “monument to a glass of water,” was cited in our discussion as an extremely poignant example of what a prototype for a monument could be like. This concept, like a many of the others included in the show, works to redress the skewed ideological assertions embedded within the monument’s usually over-bloated iconographic presence.

Every era must confront its truths, and in our time the controversies swirling around the overbearing monument have come to influence our cultural debates and direct our social media feeds to an extent that we can’t deny something must be done. Should we quietly remove the offending monument from sight, and if so will this act succeed in clearing our memory? Or should we make spectacle of the monument, blast it full of holes, chop it to bits, sink it in the bay, stomp on its head? Will such an act succeed in being sufficiently cathartic? There is always the possibility that by leaving it alone, ignoring its presence, we might repress whatever uncomfortable feelings we might have for said monumental atrocity without having to act at all.

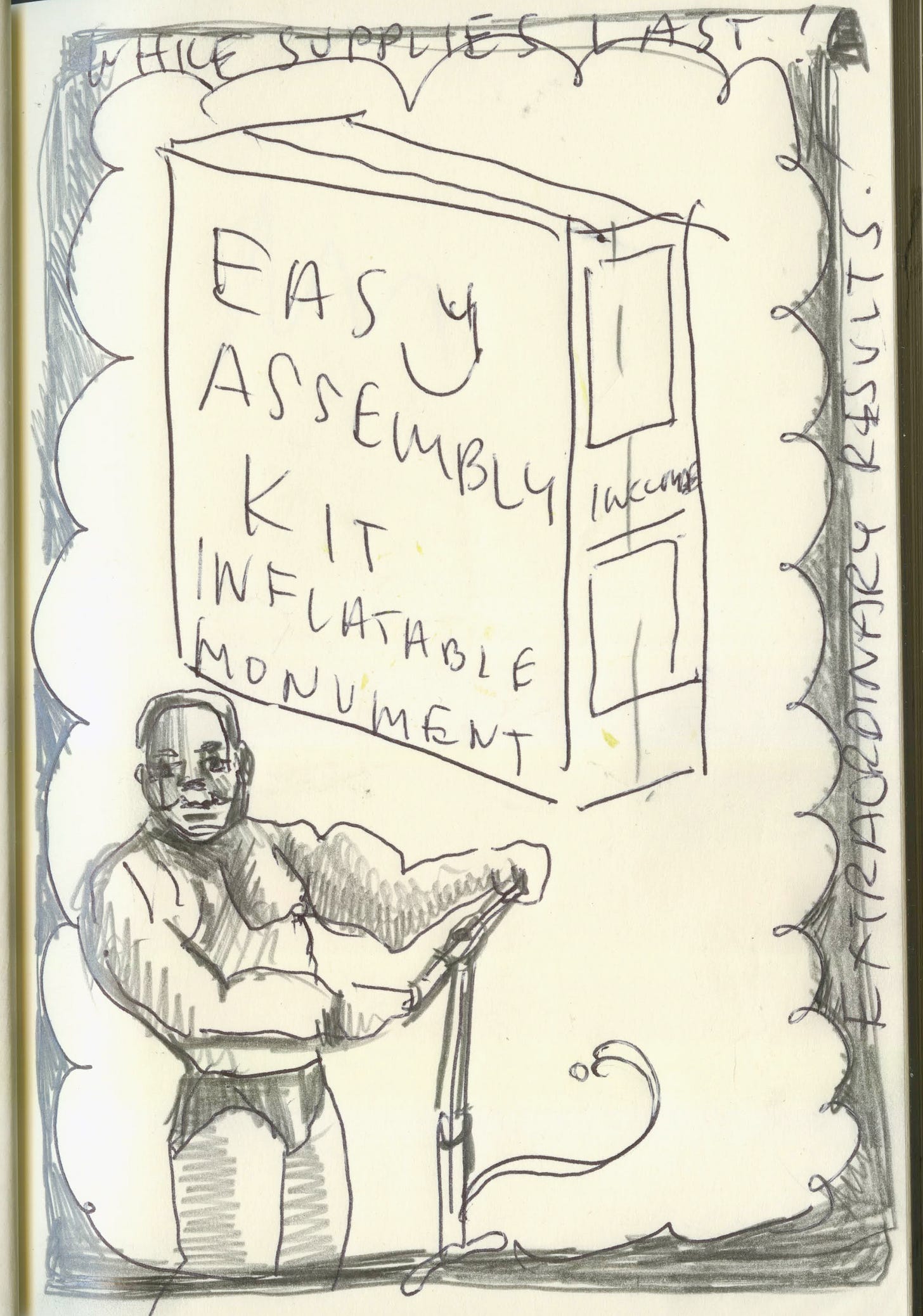

What I suggest doing is to establish a set of suitable methods capable of adequately domesticating the monument as such. To this end, an existing monument can be engaged, modified or harnessed to critically alter the original message, such as painting it like a cartoon or capping it off with a traffic cone. A second approach would be to conceive the monument not as something permanent but as something temporary, ephemeral, performative, taking inspiration from the convention of the tragic event, where the public displays its compassion and solidarity by immediately erecting walls of flowers or placing mementos. And then there is always the possibility to create something new, to conceive alternative kinds of monuments that address issues closer to today’s complicated zeitgeist.

And that is where I stand at the moment. I believe that all three approaches are necessary: existing monuments whose rhetorical image is out of touch with our contemporary mores should be confronted and critically addressed though not necessarily torn down. Just as well, I think we should consider temporary live commemorations and performances as significant non-permanent manifestations of community solidarity and consensus when we are forced to confront the extraordinary. Such a strategy could help avoid devolving into some kind of monumentally arrested development. Many of the concepts I have designed in these last few years, based on my travels to post-conflict zones and visits to country’s with tensely divided populations are meant to be considerations on the art of humility, of non-aggression, and compassion.

Making public art is a tricky exercise, understanding how space can become place is equally challenging, especially when increasingly physical space competes with virtual space. What need might there be for a 3 dimensional solid representing something even moderately symbolic? Is it so farfetched that we might see the day when a community comes together to erect the Monument to a Minimum of Hope?

While I was packing up the scrolls of drawings, linoleum prints, the handmade books, the inflatable temporary monuments and unplugged the animated video Podcast on Monuments, I turned around and realized I had almost forgotten to take with me a large watercolor I made that sat in the gallery’s front window. I practically neglected to pack up my proposal for a Monument to AI. The monument consists of a tall pointed tower that sits atop a one story building containing an unemployment office. I was left wondering if I had violated one of my own principles, that is, not to delve into the disproportionate. But then again, I have to admit, its a message that hits home.

The Monument Podcast, where the host, Terrence Collina is joined by the monuments expert Dr. Tom Flame in this brief but informative taped discussion. Produced by YellowGloveLab, Directed by Peter Lang, edited by G. Penzo. Exhibition Curator: Carmelo Baglivo. With Italian subtitles.

For a digital gallery view of the exhibition and images of the work displayed go to this link: Monuments counter Monuments.