Volterra's long shadow. The Tuscan hill town that casts its singular history into the present.

I took a detour on my way through Tuscany to stop in Volterra. With 3000 years of living history the Etruscan city never ceases to defy expectations.

I had been to Volterra before, but I forgot how hard is it to actually get there. With no direct train routes and complicated bus connections the easiest way there is by car. I parked outside the city walls and walked into the town through its famed Etruscan gate, “La Porta all’ Arco,” one of the oldest and most mysterious stone portals still standing from the Etruscan era. Three ominous heads are fixed to the archway and gaze out towards the valley below.

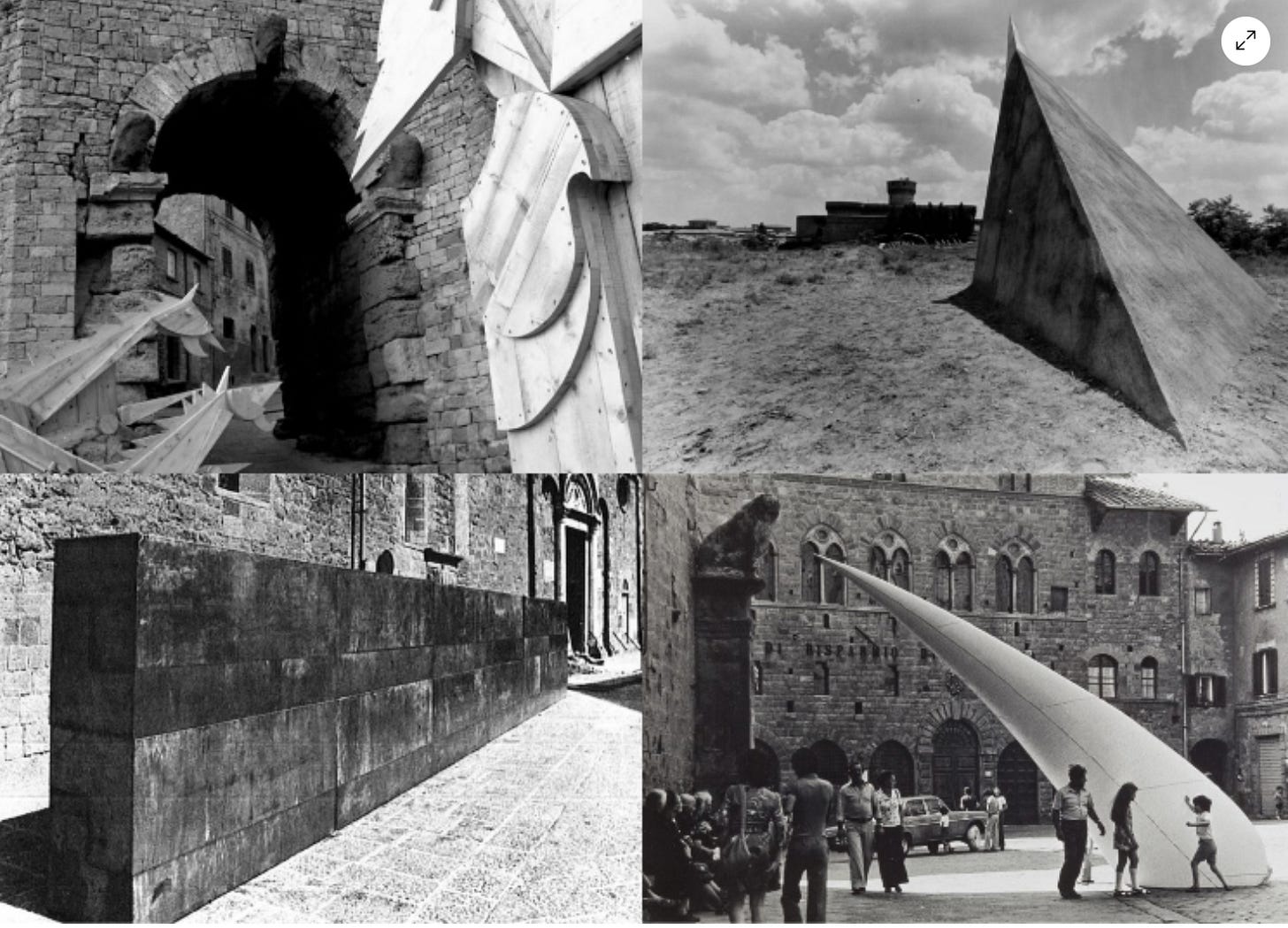

A few things caught my attention as I walked around that made me think my visit to Volterra would be more than just a stroll through the past. I wasn’t quite prepared for what I saw on my drive in, like the over-scaled circular sculptures that seemed to hover over the surrounding landscape. I also found it odd that in such a small center you need to pay for entry tickets to see either the octagonally shaped baptistery or the Duomo, both early gems from the 12 century. You have to first visit the museum that occupies another 12th century structure that once served as a medieval hospital. The ticket gets you into everything, but while I was inside the museum I found a small but intriguing exhibit on Volterra’s contemporary artists.

Why does a historic place like Volterra, modest in size and relatively isolated, feel more like a regular city? Rounding the corner, I discovered a small bookstore crammed to the top with used books, art and photo catalogues, arcane history publications, classic anthologies, even record albums, run by Simone Migliorini, publisher and artistic director of the International Festival at the Roman Theater in Volterra. While he climbed up and down his moving ladder, he gave me a talk on what makes Volterra such an active cultural hub. Migliorini ran through a list of prominent names in theater, in cinema, in the arts and design who have been frequenting the city over the last 50 years. So indeed very cosmopolitan, but why?

Volterra has been around for a very long time; it is one of the oldest continuously inhabited centers in Italy. Velathri, the city’s original Etruscan name, dates back to about the 8th century BCE and belonged to the Dodecapolis, the Etruscan League of Twelve. The city gradually became romanized, over time acquiring the latin name of Volaterrae. Its hard to miss the numerous Roman archaeological sites around the city, including the well preserved Roman theater—currently serving as a classical backdrop for contemporary theatrical events and festivals like the ones directed by Migliorini.

Jumping a couple hundred years ahead, following the Roman Empire’s dissolution on the Italian peninsula, the perspective changes radically. Growing trans-regional trade routes and a new merchant based economy forces major societal shifts. Volterra leads these trends, reconstituting itself as an independent city-state with its own self-ruling government. In the process, Volterra invents radically new kinds of urban fixtures, including a novel hall of governance. Non-domestic and non-ecclesiastic the Palazzo dei Priori sets a significant architectural precedent. Following Volterra’s lead, similar public structures would crop up in other newly formed independent city-states across Italy, including Florence, Siena, and Perugia.

For me, this is already a big deal to experience three historic eras compacted together into singular urban center. There is also a Renaissance layer, but lets say for expediency’s sake, I’ll skip over that one. Its a kind of dark historic parenthesis, when the Florentines brutally conquered the city, and buried an entire neighborhood under the foundations of an immense fortification. This colossus, the Medicean fortress, has been put to use in more recent times as a men’s penitentiary. The other sprawling institution to leave its mark on the city is the Manicomio di Volterra, the psychiatric hospital, the largest of its kind in Italy.

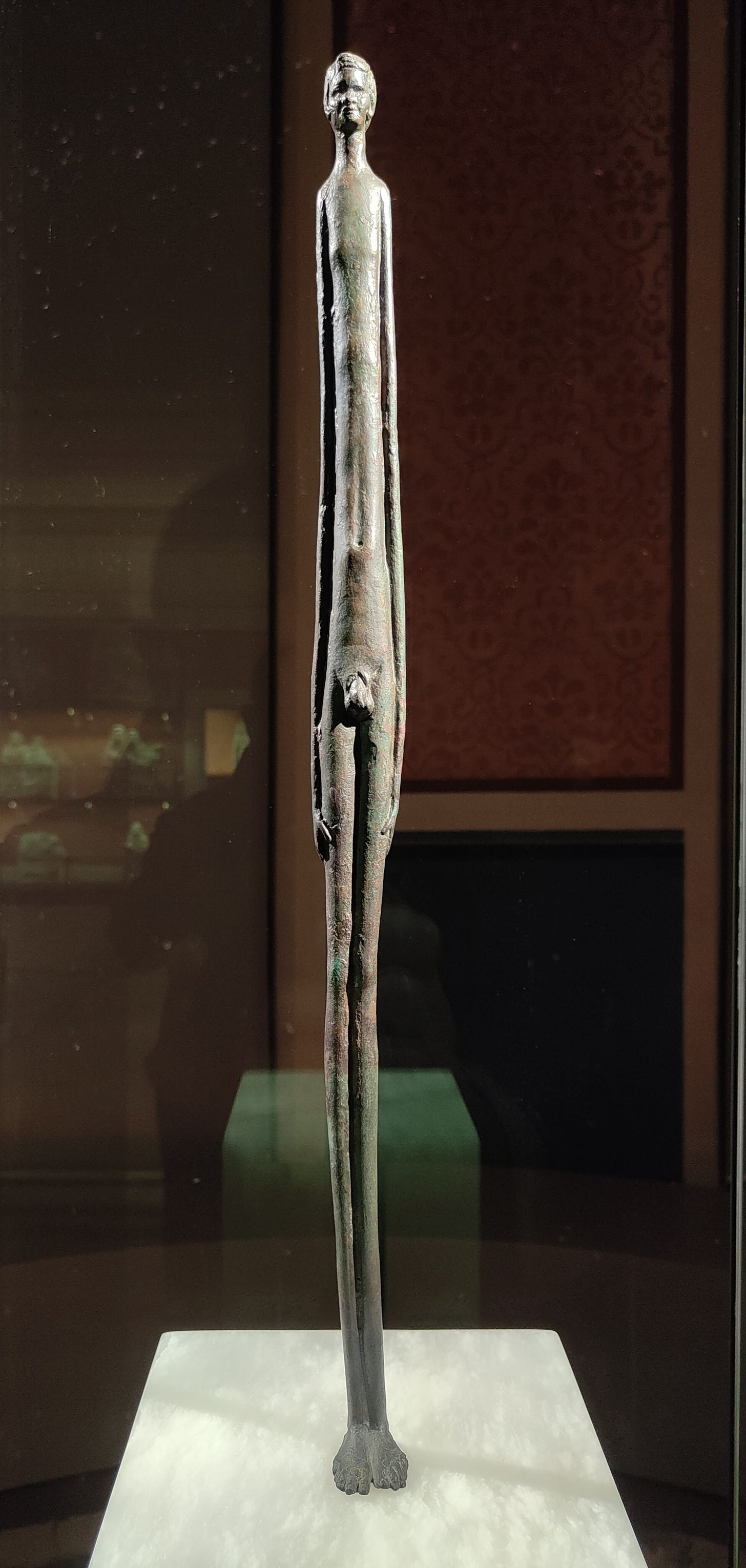

To unravel Volterra’s current secret for success, it helps to follow the threads that tie the past to the present. Take for example the Etruscan statuette “Ombra della sera,” (the Shadow of the evening) on display in the Museum Guarnacci. Dating roughly to the third century BCE, this tall skinny bronze votive most likely inspired the work of Alberto Giacometti. The Swiss born sculptor created similarly haunting humanlike figures that he introduced back in the late forties.

There are lots more threads like these worth examining. Take for example the mannerist painting by Rosso Fiorentino, “Deposition from the cross,” recently restored and on display at the Pinocoteca Civica. I have to agree with my friend’s comment that the painting, as it looks now, more closely resembles a “bubblegum wrapper.” Anyway, the theatrical composition of Rosso Fiorentino’s masterpiece was adapted into a tableau vivant by Pier Paolo Pasolini for an odd cinematic commission. In 1963 the director was invited to contribute to a film project bringing together Pasolini with Roberto Rossellini, Jean Luc Godard and Ugo Gregoretti. A kind of anthology, it was called Rogopag (the film’s title combines the first two initials of each filmmaker: Rossellini-Godard-Pasolini-Gregoretti).

Pasolini wrote and produced La ricotta, a film within a film, where the role of the director is played by Orson Welles. The story is about the making of a movie on the life of Christ, hence the scenes replicating Rosso Fiorentino’s Deposition. A few of you might be familiar with Bill Viola, the American video artist, who reenacted a work by Pontormo, a close cohort of Rosso Fiorentino, for an exhibition at the Venice Biennale back in the nineties.

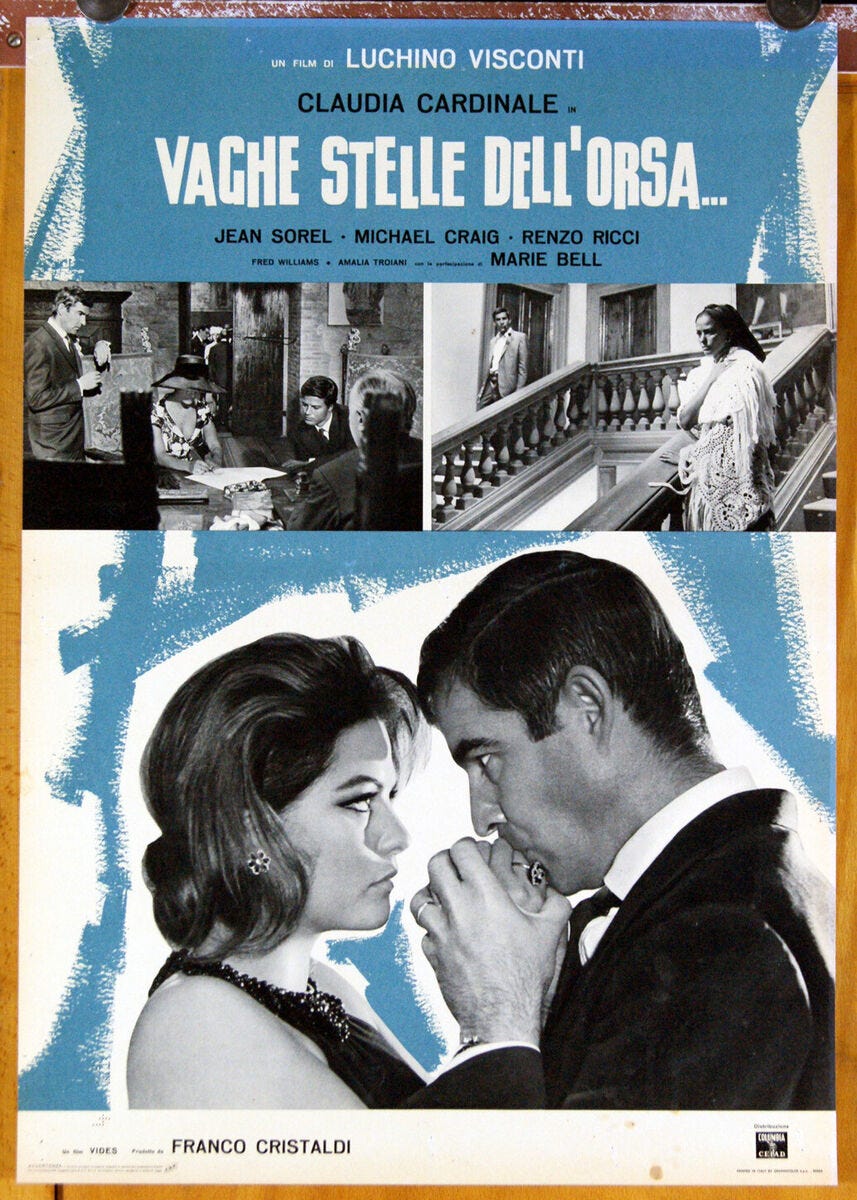

There were also a number of great films made in and around Volterra, like Luchino Visconti’s Vaghe stelle dell’ Orsa… released in 1965, about a woman-played by the actress Claudia Cardinale- who returns to Volterra to create a memorial to her father, a scientist killed in a concentration camp during the war. There is also the pseudo religious film Camminacammina by Ermano Olmi, about the three magi and their spiritual journey through a medieval landscape. The film, presented at the Cannes film festival in 1983, used Volterra as its principle urban backdrop.

But I was most intrigued by a little know artistic event that swept through the city in 1973. These were a series of site specific, environmental actions and conceptual performances that took place within the city limits and were meant to engage the local community. The project, Volterra 73, ran for a relatively short period, from July 15 to September 15, and featured Sculture, ambientazioni, visualizzazioni, progettazione per l’alabastro. (A rough translation: sculptures, site-specific installations, visual media and designs for alabaster). The intention underpinning Volterra 73 was, according to published notes by the curator Enrico Crispolti, the union of the city with its inhabitants brought about by an assemble of artists and artist collectives from Milan, Rome, Florence and Volterra.

Most importantly, the idea was not to colonize the city’s patrimony from the outside, but to liberate it from the inside. These concepts were pursued in all honesty: the projects developed by the artists, who Crispolti preferred to call “operators” focused on the psychiatric wards, on the Medicean fortress, on the city’s public realm, the city gates and architecture, on the local industries, and on the artisanal shops that produced the historic and highly coveted alabaster objects.

I had the chance to talk to Sergio Borghesi, the artist, curator and native Volterran, who was one of those involved in the making of Volterra 73, and who offered to give me an inside take on how the project came together. When I asked Borghesi how Volterra 73 took root in the city he cited the artist Mauro Staccioli, whose image of the circular Ring tops this newsletter. “Staccioli began by creating a few sculptural installations in the city in 1972, and then he had the idea of making a much bigger action that would bring together other artists, critics, sociologists, and of course the participation of the townspeople.” From what I could gather, the city was abuzz in activity for months on end. Just how all this came together is certainly a story worth retelling.

I plan to take a deeper dive, hopefully relatively soon, into this somewhat forgotten urban happening that was Volterra 73. I’ll keep you all posted!

NOTES, CITATIONS:

The English writer D. H. Lawrence visited Volterra and the surrounding countryside in late April of 1927 accompanied by his wife Frieda and their American friend, the artist and spiritualist Earl Brewster. Lawrence was sure he saw Etruscans walking the streets alongside them.

Giabelli, M. (2024). Pier Paolo Pasolini e il tableau vivant: riflessioni metadiscorsive sull’immagine del Sacro e la sacralità dell’immagine in La ricotta e Il Decameron. La Diana, (3), 37–59.

Rovesciamento di senso della pittura sacra di Rosso e Pontormo nella “Ricotta” di Pasolini. Dalla tela alla pellicola. La pittura sacra ne “La ricotta” di Pier Paolo Pasolini. di Sabrina Crivelli www.artribune.com – 11 novembre 2017

Mauro Staccioli, https://www.finestresullarte.info/en/works-and-artists/mauro-staccioli-s-sculptures-in-volterra-experiences-that-become-art-in-the-landscape

Volterra 73. https://www.toscana900.com/volterra-73-un-progetto-di-enrico-crispolti-e/

I appreciate the generous advice I received from Simone Migliorini the director and founder of the International Festival at the Teatro Romano in Volterra (we met on November 8), and from Sergio Borghesi, artist and curator. We spoke via telephone on November 13. I also want to mention an overall great place to eat while I was researching this Substack, the Vecchia Lira. My thanks also goes to G. Penzo, whose idea it was to spend a few days in Pomaia, a peaceful retreat not far from Volterra.