The Lazarus effect: how one ancient city in Italy came back from the dead with the help of some good marketing and a small entry fee.

Civita di Bagnoregio in the province of Viterbo is better known as the “dying city.” It has been falling off its foundations for centuries. But is there really life after death?

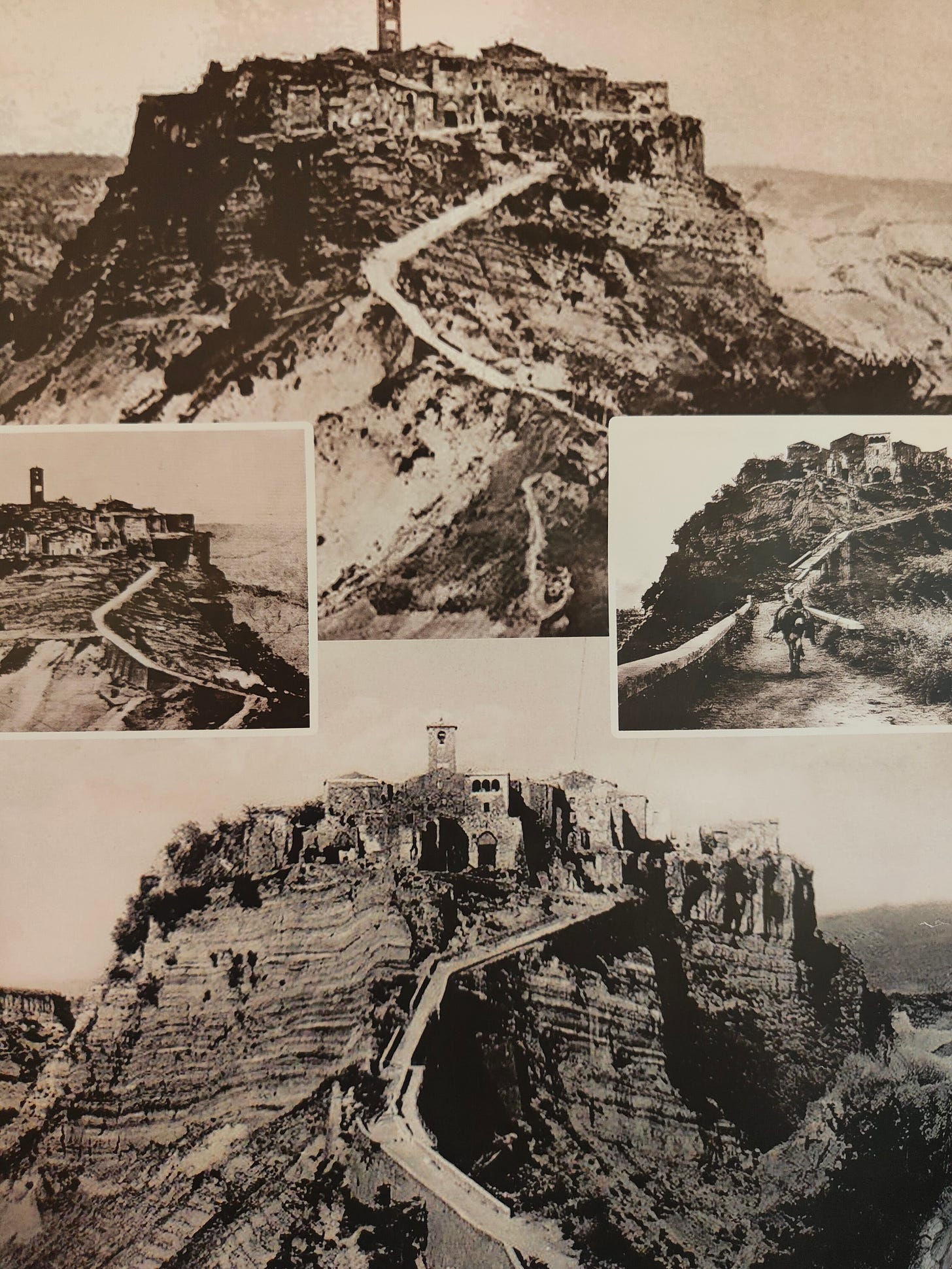

When a city dies, it falls into ruin. But what about a city that keeps on dying and dying until it seems more comatose than alive? Evidently, Civita di Bagnoregio, the “dying city,” isn't totally dead yet: founded more than 2500 years ago, historically of Etruscan origin, the city continued to grow and expand through the Roman period until it morphed into a medieval town of some renown. Nonetheless, the city's precarious existence was tied to its extremely pliant and fragile seismic landscape: There can be no question that Civita's geology was by far its worst enemy, the volcanic tuff and clay underbelly was constantly subject to violent earthquakes and devastating landslides—even the winds could turn ruinous.

Piece by piece, layer by layer Civita di Bagnoregio fell back into its surrounding Badlands (Valle dei Calanchi,). By the late 17th century an earthquake severed the only land-bridge connecting Civita to Bagnoregio, formerly its suburb, and from then on the city hemorrhaged residents, losing its families along with its only means of economic survival.

But the slow death of Civita never did reach a terminal state, as the native writer and Germanic scholar Bonaventura Tecchi famously predicted. His pronouncement would prove premature, thanks to the construction of a resistant concrete and stone bridge built in 1965 that helped Civita regain its vital lifeline to the outside world. Nonetheless, scenes of the city captured in "Contestazione Generale,” directed by Luigi Zampa and starring Alberto Sordi, offer scant proof the city was making a comeback by the time this film came out in 1970.

It took a series of major landslides beginning in the early 1990s to force civic leaders to invest in a truly practical recovery plan. In 1998 an engineering solution of sorts was developed in which seven hollow core structural columns were to be inserted inside the city's western cliffs. The process looks similar to the kind of tooth implants you can get at the dentist's. The vertical buried columns would allow for a series of intertwining steel ligatures to be woven into the shifting subsoil, and voila! A solution was finally at hand.

A Guardian article written in 2017 picks up the story from here. According to the author, Angela Giuffrida, “A series of landslides in 2014 and 2015 saw some of its medieval properties plummet into the ravine when the sides of the volcanic outcrop gave way. Geologists have described it as melting like an ice cream. However, the disaster encouraged a group of Italy’s cultural heavyweights, including Oscar-winning composer Ennio Morricone and director Bernardo Bertolucci, to back a petition calling for Civita to be given world heritage status by Unesco. The regional government of Lazio pledged more investment to preserve what was becoming increasingly recognised as a cultural and historical gem…” While the World Heritage status is still on the table, the city is on Italy's list of “Borghi più belli d'Italia (most beautiful villages in Italy)”

Francesco Bigiotti, the mayor of both Civita and Bagnoregio and who was profiled in the Guardian article, took the bold step of charging a entry ticket to the city early in 2013. It's still obligatory, and according to Bigiotti, it hasn't dampened in the least visitor attendance. Rather, the toll allows the local government to eliminate communal taxes for its citizens. And the income also defrays the costs to monitoring and maintaining conditions in Civita as things fluctuate over time. Meanwhile, the most recent technological advance is a new satellite observation system, run by Cosmo Skymed, the Italian Space Agency, that should begin to provide much more precise ground observations in the near future.

I feel like I should run through the paces: I paid my entry ticket, walked across the narrow foot bridge, passed through the historic Etruscan gate, and shuffled my way into the historic town center. If I think about how the city looked back when they made the film Contestazione Generale, where we see Alberto Sordi in a priest's garb riding his motor-scooter around a dusty Piazza San Donato then I admit the city has changed dramatically. On the day I was in Civita I was surrounded by a mass of tourists, with shops on every corner, and cafes spilling over the sidewalks filled with people sipping orange Spritzes.

With this many people all over the place the city indeed looks vivacious, but only in appearance. Tourists on their own can't make a city come alive. So Civita, the "city that is dying” is not falling to pieces like it once was but is, instead, suffering from another kind of death, death by over-tourism. Not that I think civic leaders of Civita di Bagnoregio are willingly going to renounce their catchy slogans and abandon their successful marketing campaign simply because Civita isn't moribund anymore. Lazarus was resuscitated only once; how many times can Civita di Bagnoregio be revived before there is no more soul to give up?

I wondered, after meandering around the city for a little bit, which one of these magnificently restored medieval houses belong to Harry Styles? I need to do some more research next time I'm back.

Postscript: On the subject of Lazarus, I discovered the Italian language film “Lazzaro Felice” (Happy as Lazzaro), directed and written by Alice Rohrwacher, while I was researching this newsletter. Rohrwacher received for this film Best Screenplay Award at the 2018 Festival de Cannes. Several scenes from the movie are set in the Badlands around Civita di Bagnoregio, but what touched me the most is the way the main character Lazzaro, played by Adriano Tardiolo, remains unchanged while his character lives once in a feudal past, and, when reanimated after an unknown length of time, again in an equally fraught present. I realized, watching this film, that no matter how much one remains the same, the surrounding world won't stop in its place.