MAK the Life: a cutting edge design museum in Vienna is full of unusual domestic treasures. I didn't expect Sottsass' grey units made for MoMA in 1972 to be two of them.

On a recent trip to Austria I had just enough time to poke my head inside the MAK - the Museum of Applied Arts in the heart of the capital. I was in for a real surprise.

Last week I left Rome behind for a 3 day trip to Linz, where I had been asked to give a seminar on mapping utopias for the Institute of Space and Design at the Kunst Universität. (*) Linz is a peculiar place, with a lugubrious past and a techno present fused to the Ars Electronica festival. The last time I was in Linz was back in 2002, when I was part of a gathering of Asian and European urbanists, artists and architects, organized by the group Urban Flashes, whose main theme is spontaneous urbanism. We explored ways Asian street life activates urban neighborhoods in ways that could potentially benefit cities like Linz, whose daily urban life left much to be desired.

The trip to Linz afforded us an afternoon walk in Vienna, a good excuse to explore the Austrian capital. Vienna comes off as a prominent 19th century European capital city whose monumentally exaggerated proportions can only make sense if there would still be an entire Austro-Hungarian Empire plugged into it. In compensation, the city has gone a long way to serve its local inhabitants, providing housing and amenities that have made Vienna one of the most livable cities in the world. These achievements have been brilliantly highlighted in this year’s Austrian Pavilion at the Architecture Biennale in Venice (More on this and the Agency for Better Living in a successive newsletter).

True Vienna no longer aspires to Imperial grandeur, but instead the style of contemporary architecture going up around the capital is definitely a goulash of current global architectural trends. Nonetheless, Vienna is like a multi-layered Sacher torte, so its not that difficult to map out a psychogeographical tour around the city, across the boulevards and streets, strolling the parks, or from the inside of a particularly good Viennese Café. Serendipitously, our choice to go to the Café Prückel put us right in front of one of Vienna’s great museums, the MAK, the Museum of Applied Arts. The museum is best known for its 19th century Viennese design collection but as luck would have it that collection was closed for renovations. Instead, the MAK has several temporary installations on offer. The exhibition Water Pressure is based on solid concerns about longterm water sustainability but is too didactic to hold one’s imagination for long (MAXXI’s “Something in the Water” curated by Oscar Tuazon is also a treatment on water, but is much more credible simply because it leaves the messaging to artists).

Down in the museum’s vast basements I turned my attention to the exhibition “BLOCKCHAIN:UNCHAINED: New Tools for Democracy.” It was chock full of creative digital prototypes, exploring key sectors in today’s digital ecosphere and how they can be hacked for the better social good.

And then I turned the corner and walked into MAK’s permanent design collection and did a double take: on display among the cool lamps, weird chairs and extravagant designer paraphernalia one pair of objects stood out like rare tiffany lamps in a junk shop: two full sized grey plastic furnishing units by the renowned Italian designer Ettore Sottsass Jr.. In all the years I have been working on postwar Italian design and more recently on one exhibition in particular, Emilio Ambasz’s Italy, the New Domestic Landscape at MoMA, I had never seen these plastic units in the flesh.

Ambasz split the 1972 exhibition into two parts, one on Italian design products and the other on a set of commissioned environments. Ambasz was looking to set some significant critical challenges: the Objects were divided into “conformist,” “reformist,” and “contestatory” categories, while the Environments were presented under more loosely labeled subjects: “design as commentary,” “pro-design as postulation,” and “counter-design as postulation.”

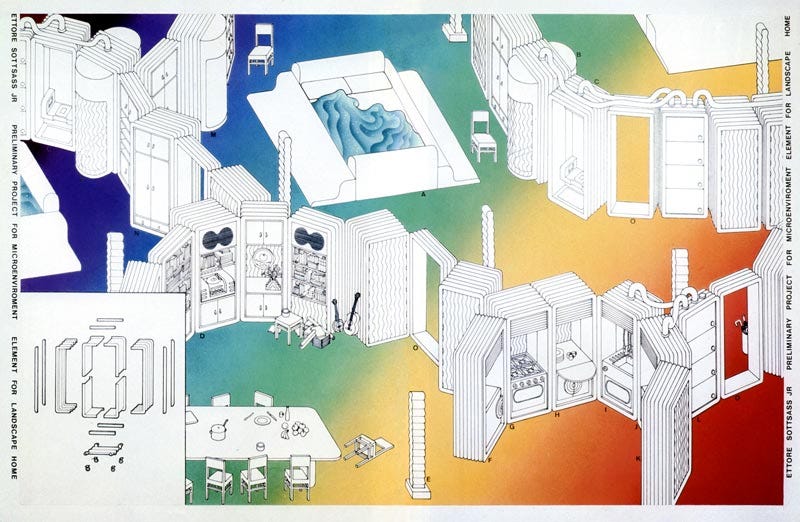

Sottsass’ contribution, under the rubric “design as postulation” was made up of a series of free standing modular environmental units that could either be locked together or arranged into clusters, depending on the users’ demands.

Here’s a bit of background: Emilio Ambasz’s exhibition at MoMA from 1972 had never been properly reconstructed because the show didn’t quite fit together, it was like a puzzle with a lot of missing pieces. Fortuitously, while I was doing some followup research on another show around 2006, I came across a number of original VCR cassettes that were an integral part of the New York MoMA show. The video cassettes were presented to me while I was working in the studio archive of Superstudio, the Italian Radical design office that achieved international renown in the late sixties.

The videos turned out to be a missing link of sorts: there were in all 10 different short films from 10 different designers, that provided important clues to unpacking Emilio Ambasz’s main exhibition premise. And they became the centerpieces for a new exhibition “Environments and Counter Environments. "Italy: The New Domestic Landscape,” MoMA, 1972 .“ Basically an exhibition on an exhibition, the project was curated by yours truly and two close colleagues, Mark Wasiuta and Luca Molinari. We assembled a pretty comprehensive collection of original archival documents, models, photographs, film stills, drawings, lengthy interviews and of course these film shorts.

Our exhibition generated quite a bit of interest, beginning with MoMA. The exhibition was launched in 2011 in New York at Columbia University, and then travelled to a number of international venues: the D-Hub at Barcelona, SAM at Basel, the Arkitekturmuseet at Stockholm (now known as ARKDES) and finally the Graham Foundation in Chicago.

Coming back to Ettore Sottsass, the Milanese artist/designer/photographer envisioned for his series of modular plastic domestic elements a maximum of possible living scenarios, unrestrained by fixed objects or divided rooms. I wrote back then for our unpublished exhibition catalogue that the film, which played on a TV set next to Sottsass’ units, provided a clearly “anti-commercial but also anti-conformist message.” The accompanying film reinforced “Sottsass’ lifelong disdain for political ideologies, and his deep belief in the autonomy of the individual. The built in irony is that Sottsass’ units are not intended to lead to the good life, but by presenting his object universe as a struggle Sottsass’ message perhaps rings with greater truth.”

This contradictory messaging was fittingly exploited by the film’s director Massimo Magri who created a very Brechtian type theater denuded of distracting contexts. As I then noted: “the film as such succeeds in presenting Sottsass’ units as the only furnishing necessary to live out ones life.” And given the way things are going these days, if we want to get beyond the current climate of fear and mistrust, we should get back to the basics, we should start by reexamining the way we live our domestic environment.

(*) I would like to thank Lorenzo Romito, Professor at the Institute for Space and Design for inviting me to Linz, and also Andrea Curtoni and Giulia Mazzorin and the students at the Institute for their involvement support. Utopia, especially in these times, is a tough topic.

NOTE: I made some initial attempts to contact the MAK curators in charge of the museum’s permanent design collection to get the full story on the acquisition of these Sottsass units. I am still waiting for a response. In the mean time, if any of my readers could help me with this inquiry please contact me directly.