Megalopolis: the way of the architect and the trouble with stereotypes.

I went to see Coppola's Megalopolis, and I found, buried deep inside the convoluted story, strains of an emergent utopia. But as expected, the character of the architect remains locked in the past.

What caught my attention about Francis Ford Coppola’s latest film Megalopolis was the image of Adam Driver raising a T-square above his head like a crucifix. With that kind of symbolic image plastered around town I knew I had to see the film, and I couldn’t care less what the critics had been saying. I decided to haul myself over to the Nuovo Olimpia next to Piazza di Spagna, which is one of the few cinemas in Rome where movies are shown in their original language.

I was particularly curious to size up the film’s leading character, embodied in the figure of the architect. What kind of role does the architect—still a male gendered character according to Coppola—play in this grand society saga? Architects are usually represented in movies as passive male idealists who serve as romantic foils to move along the storyline. Clearly things aren’t like that in the real world anymore. There are far more women working in the field than ever before, and the number of male star architects seems to be gradually receding. Unfortunately that’s not the impression you get when you watch Megalopolis.

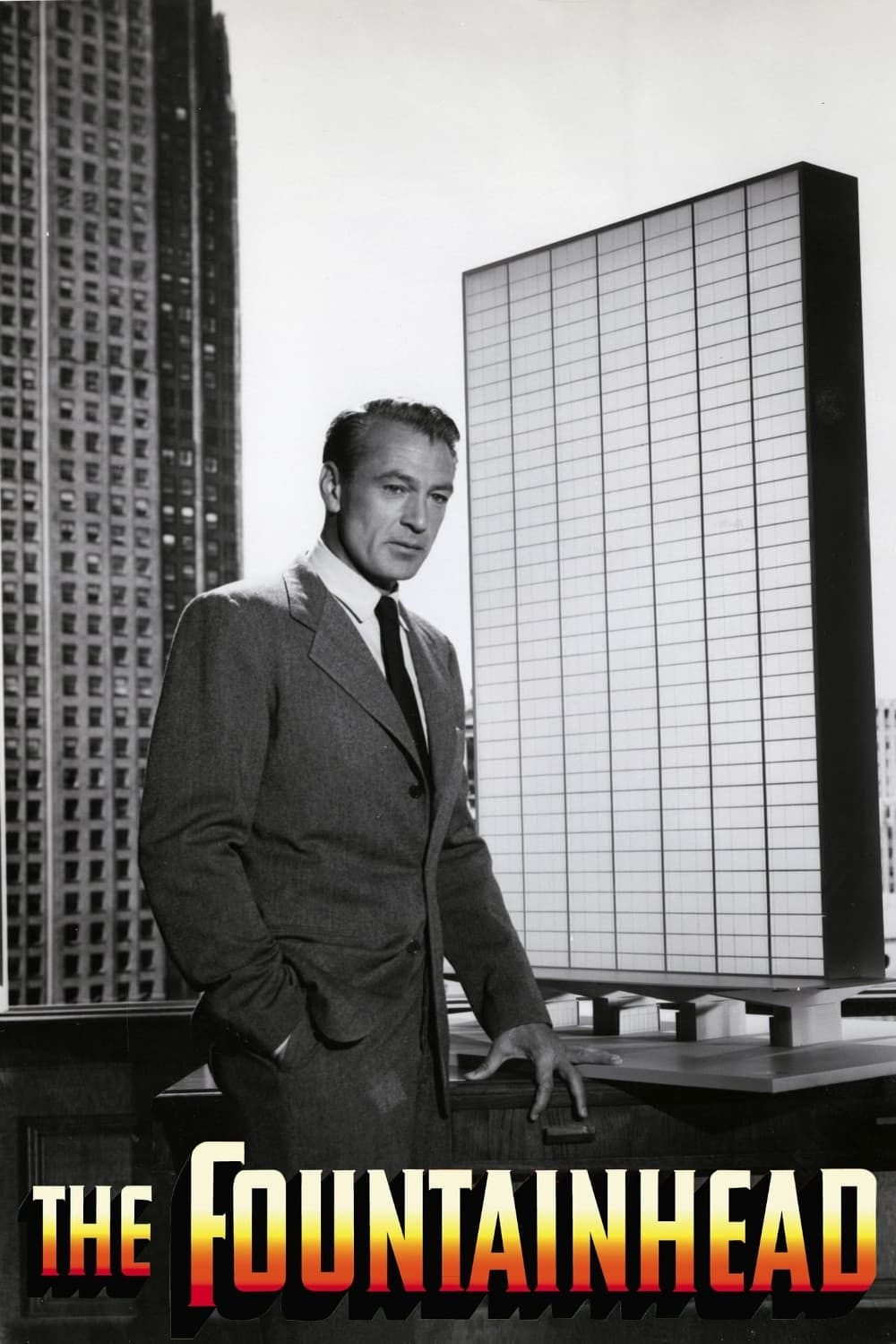

There is a lot of cinematic history centered on architects. One of the towering figures representing the profession was crafted by King Vidor in his 1949 rendition of Ayn Rand’s the Fountainhead. Gary Cooper stars as a headstrong but dedicated architecture visionary who would rather dynamite his buildings and serve time in labor camp than allow miscreant clients from altering his purist designs.

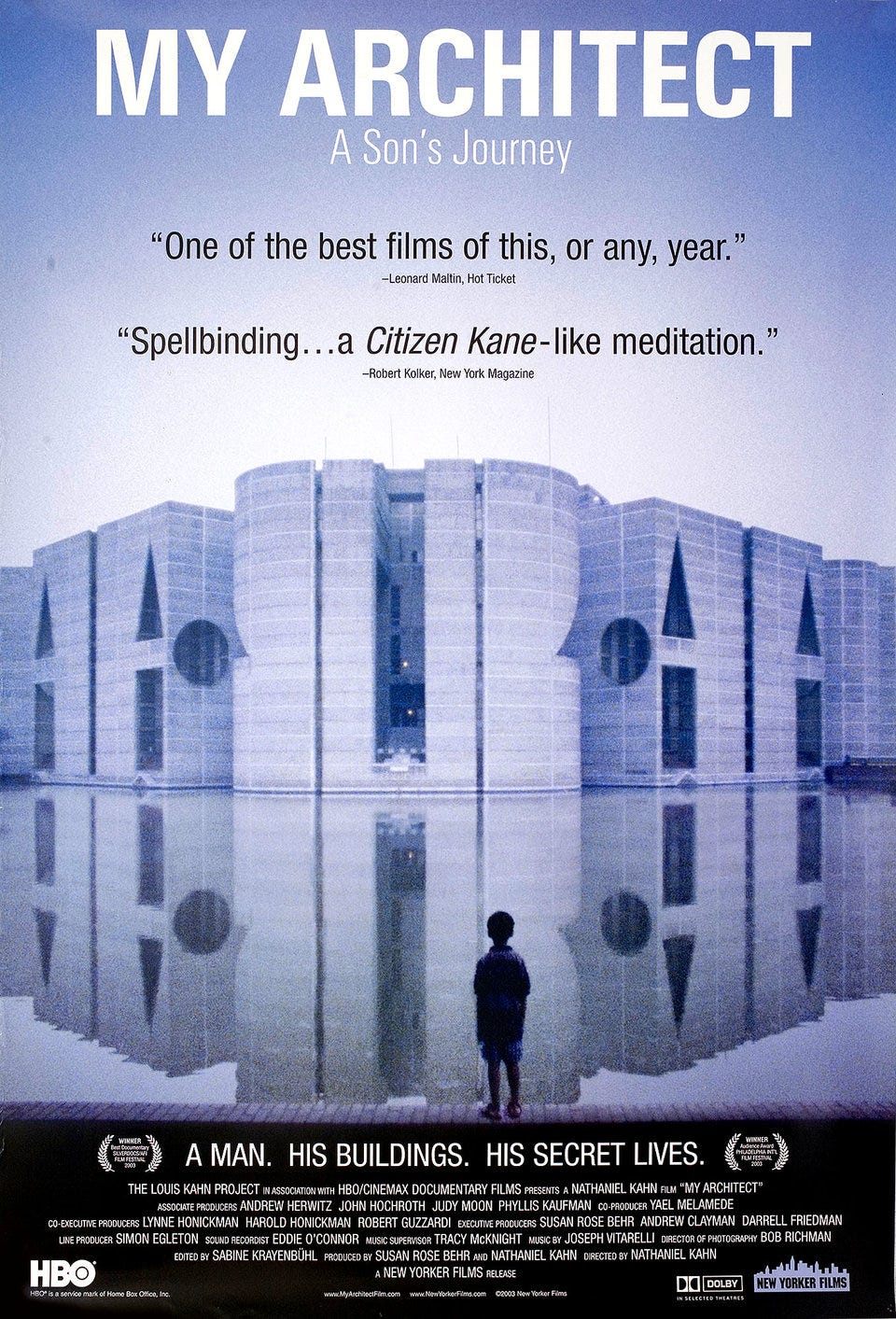

Of the many films in this genre, two worth mentioning came out the same year, in 1993: a romcom directed by Nora Ephron based on a screenplay she co-wrote, Sleepless in Seatle, featuring Tom Hanks as the widowed architect and Meg Ryan as the love interest; and Indecent Proposal, directed byAdrian Lyne and written by Amy Holden Jones. The latter film features a rich guy played by Robert Redford, an architect, strapped for money played by Woody Harrelson and his pleasing wife, played by Demi Moore, whose beauty will gain them the money to complete construction on their super cool modernist house. Tucked deep in the film is a lecture by Harrelson to his architecture students about the meaning of a brick, an anecdote inspired by the world renowned Estonian born Philadelphia architect Louis Kahn.

Louis Kahn was no slug in bed either, and it is worth seeing his estranged son’s 2003 film, My Architect, a fascinating and deeply personal bio-pic that shines a light on the true struggles and rewards of an architect with great design principles, though far more questionable family values.

In fact, since this film on Kahn was released a slew of others biographies by disgruntled or spoiled offspring were produced, offering opportunities galore to get to know this or that star architect. For what its worth, I still prefer the fictional kind. And luckily, there is one TV show where the architect does not play a hopeless romantic visionary, but instead comes across as a cold blooded killer, driven to protect the urban development project he has dedicated his life to. Blueprint for Murder is the last episode in the first season of the Lieutenant Columbo series, directed by and starring Peter Falk. Apparently it takes a story about a mad architect to introduce to the audience the real nuts and bolts details that go in to actually making a building.

So where does Adam Driver’s character Cesar Catilina fit in all this? How “good” an architect is he? Megalopolis is supposed to be a new utopian neighborhood, and is, according to the storyline, Cesar’s greatest creation. Cesar however, lives in a very dated future, not quite of the steam punk kind, nor very rational and tidy either.

Cesar’s office is in the penthouse of the Chrysler building, the ultimate symbol of thirties art deco. When he goes somewhere, he is seen chauffeured around town in a sleek Bertoni styled Citroën DS, itself one of the most revered post-war automobile designs to make it into mass production. There are plenty other objects lying about his office and his home that are lodged in the 60s , like TV sets, telephones, kitschy furniture and other home decor.

Cesar is portrayed sitting in his triangulated office crouching over his sketchbooks, pencil in hand, drawing geometrical shapes and making odd notations. Its all very stereotyped. I would have hoped Coppola would have seen Cremaster3, by the artist Matthew Barney who transformed the Chrysler building into a kind of “zombie gangster film.” Titled Death, Resurrection, and Transcendence the work spouts havoc and destruction, a sort of unapologetic confrontation with America’s hard core industrial culture.

New York city is the film’s ever-present backdrop: many of its most iconic buildings, streets and public spaces appear as significant sets. Rome the Italian capital is nowhere present, but the individual characters are dressed up in exaggerated ancient Roman fashion, giving the film a kinky hybridized style, where a toga clad elite frolic among the monuments and ruins of a rusting modernity. What is at stake for the Cesar, however is his forlorn ability to bring his vision of utopia to New York City, that doubles for the city New Rome where the film is set, but which could just as well have been Batman’s Gotham. Its a mess of a place, and utopia is the prescription everyone is somehow waiting for.

And this is the main problem with the heroic vision of the architect. Adam Driver, as Cesar Catilina, with Roman haircut and all, sets out to save his city by singlehandedly proclaiming that he alone can bring about utopia. His mantra, “don’t let the now destroy the future,” is all about those who can be trusted with the custody of the city and its people. The poor helpless citizens, accordingly, deserve being liberated through architecture, though in the film it seems like the architect is himself a pawn subjected to the whims of the ruling class.

For an odd moment, there is this chance that Cesar is actually on to something, when you see him with what could be either his students or his young assistants setting up in his studio a playground of objects that represent buildings and spaces in the new utopian city. Cesar’s new love interest, Julia, played by Nathalie Emmanuel, walks with her eyes closed through this playful maze, and sees a world made of organic structures, growing like flower petals and filled with happy inhabitants. Of course Cesar invented the one material that could make this all happen, “Megalon” —though I am pretty sure I saw something similar already developed by Neri Oxman, inside the media lab at MIT. She would have made, by the way, a great alternate to the male melancholic architect played by Driver.

While Megalon should take care of erecting all the wild fluid structures, designing for a social utopia is a completely different story. That is why the short scenes early in the film with Cesar and his black clad assistants looked so promising, because they reminded me of an earlier time, back in the seventies, when the designer Lawrence Halprin adapted the creative choreographic skills pioneered by his wife Anna Halprin to come up with a collective form of designing. They spontaneously set in motion a series of performative actions with students and community members that collectively determined the outcome of their future environments. Like the RSVP cycles, that are as close to utopian as it gets.

Unfortunately, Cesar quickly snaps back to the standard caricature of the architect, where only “he” with “his” great personal genius, can deliver a solution from the top down—literally, since he is up on the top of the Chrysler building. In the end he opens his arms and there it is, like some divine blessing, a ready made utopia, ready to be lived in by the masses. A pity, because this kind of commanding “star architect” has been around forever, and unfortunately still grabs the public’s attention. The stubborn arrogance of a Howard Roak, the architect in the Fountainhead, seems to be the model that never ceases to dominate over the urban landscape.

Can any of you out there in today’s world give me some positive examples of people making a utopian society that works? I am sure of one thing though, imagining utopia is a collective project.

POSTSCRIPT:

Francis Ford Coppola’s film Megalopolis has many serious shortcomings. His treatment of women—both on and off the set, the leaden fascist slogans and the cliché behavior of law enforcement, only reinforce this notion that Coppola hasn’t really understood the world has changed since the time when he produced films like The Godfather and Apocalypse Now. Martin Scorsese, from Coppola’s generation, nonetheless did his best to make a film that broke from past traditions. His 2023 film Killers of the Flower Moon, confronts long-held prejudices and attempts to expose the dark underside of American history and goes much further in examining the tragic underpinnings of Western history.

POSTSCRIPT 2.

If you really want to see a great portrayal of the fall of western civilization done as a provocation, a contemporary re-staging of Greek mythology reflecting the weird and wild ways of our time while remaining close to the original texts, I recommend picking up the Netflix series Kaos. Created by Charlie Covell, its a satire that brings the past careening into the present, featuring a very diverse cast, incredible dialogues, amazing locations and far-far out sets.

Peter,

Submit This review to the New Yorker magazine. That should inspire them to hire you. Do you know the 1960 film starring Kirk Douglas as an architect?

it is titled strangers when we meet. That's a fairly straightforward and realistic portrayal of architecture then, admittedly the character was not a star architect.

Another way to interpret Coppala's film megalopolis is as an analogous warning about Trump, who has often said only he can save the country.